Diarrhea in calves and prevention of cryptosporidiosis

“More often use a shovel, not a needle,” expert advises

Cryptosporidiosis is a pesky parasite that often causes diarrhea in calves, i.e. watery diarrhea, by spreading through oocysts in the animal's feces. Although it is not difficult for an experienced veterinarian to identify this problem, and cryptosporidiosis is not fatal, the disease slows down the growth of animals and requires supportive care costs.

Unfortunately, there are no approved vaccines against cryptosporidiosis yet. As American bovine HEALTH expert Jim Quigley says, “A shovel can do more good than a needle” when it comes to cryptosporidiosis.

In a series of articles, Quigley notes current world research on this topic.

“Over the past year or so there have been interesting scientific papers on Cryptosporidium infections in small calves and older cattle. Since "cryptosporiasis" is an economically important disease, I thought it would be useful to look at a few of these studies in turn.

The first came from the University of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. Researchers visited dairy (86) and beef (60) farms located in northwest Spain and collected fecal samples (594) from calves and cows. All samples were taken from healthy animals, i.e. none of the animals showed clinical signs of cryptosporidiosis at the time of sampling. The samples were stored for several days and then analyzed using molecular methods for the presence of DNA from various Cryptosporidium species.

Of the 594 samples collected, 99 were positive for Cryptosporidium DNA, accounting for 16.7%. At least one sample was positive on 45% of the farms (64 farms).

The most common species were C. parvum and C. bovis. Other species of Cryptosporidium were less common. The animals with the highest prevalence of any Cryptosporidium were calves <1 month of age. More than 80% of samples tested positive for C. parvum.

With age, the prevalence decreased, the type of organism changed. The proportion of C. bovis increased in groups 1-2, 2-12 and 12-24 months. Old cows contained several species of Cryptosporidium and could well be considered a reservoir of infection for the youngest animals.

Many studies report that C. parvum is the most common cause of cryptosporidiosis in young calves. Calves under 1 month of age are thought to be particularly susceptible due to their immature immune systems, and become less susceptible as active immunity develops.

It is also interesting to note that even though the samples were taken from healthy animals, a significant percentage were positive for Cryptosporidium in faeces. Nearly 30% of calves under 1 month of age were positive for Cryptosporidium, and mostly for C. parvum. Because C. parvum is a zoonotic disease, meaning it causes disease in both humans and calves, this should be considered for immunocompromised caregivers.

Summary. A significant proportion of calves shed Cryptosporidium species in their faeces despite being clinically healthy and showing no signs of disease. Also, body type changes with age and, presumably, maturation of the calf's immune system.

The second note summarizes research from the University of Guelph and describes the impact of C. parvum, rotavirus, and CORONAVIRUS on the health of young bulls.

Canadian scientists observed 198 bulls raised on a grain-fed veal farm. The calves arrived at the facility at 3-7 days of age from dairy farms in the area (Ontario, CANADA). Total serum protein was measured upon arrival. The calves were fed MILK replacer and switched to dry food at 56 days of age. After that, they were divided into groups until 77 days of age, when they left the study.

Fecal consistency was assessed daily for the first 28 days, and fecal samples were collected on days 0, 7, and 14. Fecal samples were analyzed for the presence or absence of Cryptosporidium parvum, bovine rotavirus, and bovine coronavirus. In addition, animals were weighed on days 0, 14, 49, 56 and 77. The number of veterinary treatments, cases of diarrhea and mortality were recorded during the 77 day measurement period. The researchers assessed the prevalence of each organism, the frequency of diarrhea, mortality, and the effect of the disease on growth.

In this study, it should be noted that the prevalence of rotavirus was very high throughout the study, as was the prevalence of coronavirus from day 7.

During the trials, many calves had diarrhea. Overall, almost 84% of calves were treated for clinical diarrhea during this study. In addition to C. parvum, rotavirus and coronavirus, calves were affected by the Dublin Salmonella outbreak during the study period. Thus, the majority of cases of diarrhea are likely to be associated not only with C. parvum, but also with several organisms.

Summary. The results of the study showed the incidence of infectious organisms, including C. parvum, when growing grain-fed calves. A high incidence is not normal and reflects the risk associated with grouping and transporting very young calves when they are most susceptible to infection by enteric microorganisms. With regard to exposure to C. parvum, the data clearly show that when calves are infected with cryptosporidiosis, they have more diarrhea, higher mortality and slower growth. That the calves were 8 kg lighter on day 77 of the study when they were positive for C. parvum on day 7 indicates a long-term effect of this organism on calf growth.

A Brazilian study looked at the risk of transmitting Cryptosporidium (especially Cryptosporidium parvum) to small calves. And I was very interested to see what these researchers found and whether their findings were consistent with our understanding of the pathology of this parasite. Let's take a look.

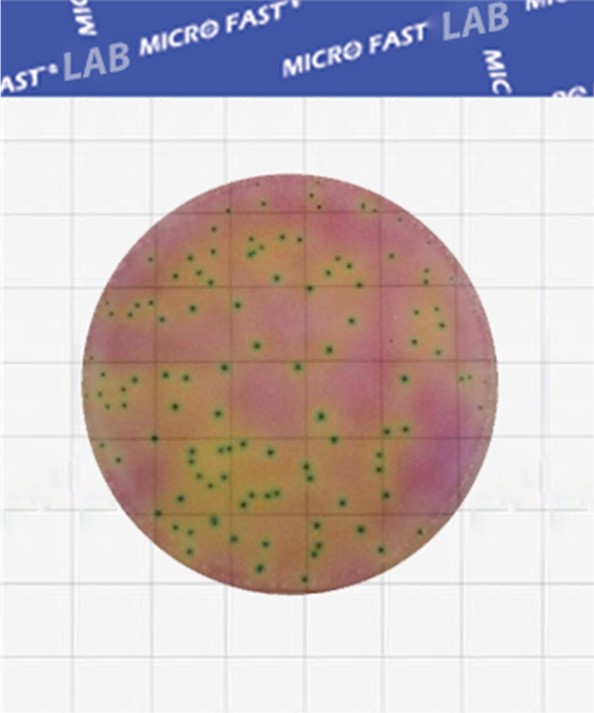

In a report from Brazil, scientists tracked the shedding of C. parvum oocysts from calves under 10 months of age in Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil, collecting 385 fecal samples and determining the presence of oocysts. They found that 25.7% tested positive for Cryptosporidium spp..

Factors that increased the risk of infection were contact with goats and sheep, use of a semi-intensive rearing system, and faecal contamination of food and water.

In comparison, calves that had contact with goats or sheep were 3.3 times more likely to be infected than calves that had no such contact.

These data are in very good agreement with our understanding of the biology of disease transmission. That is, infected animals excrete a huge amount of oocysts with feces. These oocysts can live in the environment for up to six months and become carriers of infection. When contaminated faeces (perhaps from sheep and goats) contaminate water or feed, calves become easily infected. The intensity (i.e. more animals in a limited space) of animals simply increases the concentration of oocysts in the environment and increases the number of animals potentially exposed.

Summary. In general, most of the factors that increase the risk of C. parvum infection are contact with other animals (especially apparently goats and sheep), failure to remove infected faeces from the environment, and incorrect or inconsistent cleaning protocols. The type of flooring and the weather play a role, the risk of infection is higher in warm and humid.

It is consistent with the biology of infection that floors that are easy to clean (concrete) are better in this case, as are slatted floors that remove potentially infected calf feces. Of course, if the farm does well with softer types of litter (straw, shavings, etc.), the risk of infection can also be reduced. Sanitation is the key to health.

Overall, the study is a good reminder that "you can get more done with a shovel than with a needle."